Keep Forgetting Your Password? Try This Novel Virtual Authentication Technique

First-person Virtual Maze Offers More Memorable, Harder-to Break Passwords for Infrequent Authentication

We’ve all been there. For the first time in months, you’ve been logged out of your social media account and need to log back in. The problem is it’s been so long since your last log in that you don’t remember your password. You try every combination of baby and pet name, sister’s birthday, childhood street address – nothing works, and now you’re locked out.

If only there was a better way to remember these passwords after extended periods of disuse.

Luckily, researchers at Georgia Tech have come up with a novel solution to this longstanding problem, applying an old memory technique to new technology to offer users a more effective authentication method. Known as ‘the Memory Palace, the new tool is a three-dimensional virtual labyrinth navigated in the first-person perspective.

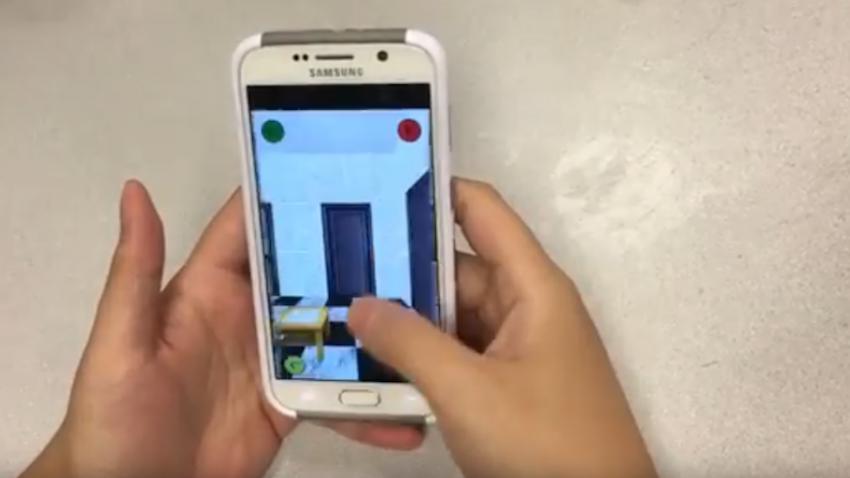

In cases of infrequent authentication, the Memory Palace works in place of an account’s password. Users create their own personal path with multiple left or right turns through a maze that must then be recreated to log in to their account. If the user makes it through the maze, similar to the one found in the old Windows three-dimensional labyrinth screensaver, they gain access.

Studies evaluating the technique showed that visual-spatial secrets were most memorable if navigated in the three-dimensional first-person perspective. They also showed that, in comparison to Android’s 9-dot pattern lock, the Memory Palace was significantly more memorable after one week, was harder to break through shoulder surfing (capturing passwords by looking over someone’s shoulders), and were not significantly slower to enter.

VIDEO: Explore 'The Memory Palace'

“Humans have evolved with remarkably persistent and fast-imprinting spatial memories, owing in no small part to our nomadic history,” said School of Interactive Computing Assistant Professor Sauvik Das, the lead researcher on the project. “Many people can, for example, clearly visualize and mentally walk through their childhood homes, even if they haven’t stepped foot in it for decades. They may only need to be shown once or twice how to drive to a new part of a familiar city.

“Our key insight was simple: Why not co-opt this incredibly strong spatial memory system for infrequent authentication?”

This visual-spacial authentication is based upon an old memory technique of the same name, also called the “method of loci.” That approach uses visualizations with the use of spatial memory, familiar information about one’s environment, to quickly and efficiently recall information. World Memory champions have applied this technique in competition for years, associating vivid images along a specific path with digits, letters, or playing cards they are required to memorize. In fact, the technique dates all the way back to ancient Greeks and Romans.

When developing their program, researchers focused on a few keys to their method. In addition to security against common attacks like random guessing or shoulder surfing, they needed the authentication secret to be memorable without much practice or reinforcement and they needed it to be deployable to the public.

“Users are unlikely to accept a solution that requires significant upfront training or effort,” said Das, an expert in a field dubbed social cybersecurity that examines social norms that impact the adoption or rejection of security techniques. “Also, the solution should be cost-effective and not require specialized hardware. Many authentication solutions have been proposed, but most fail to be widely adopted for these reasons.”

Existing solutions fall short in these requirements. Biometrics, like a thumb print or facial recognition, require specialized hardware that can be expensive for infrequent use cases. PINs and graphical passwords have problems in long-term memorability without frequent reinforcement, or are otherwise vulnerable to shoulder surfing.

“The Memory Palace addresses each of these concerns with a proven memory technique that can hold up over time but is not easily stolen,” Das said.

Das provided a handful of potential instances of infrequent authentication. Perhaps a session persists for a long period of time, like social media accounts, or a user must log in on a different device than normal, like a Netflix account on a web browser versus a smart TV. Other situations include occasionally-accessed resources, like a conference room secured with a smart lock, or as a fallback authentication method where a secondary secret is needed to recover access to an account where the primary secret has been compromised.

To deploy to the public, an app could implement the Memory Palace as a means of authenticating users. Alternatively, an operating system like Android could implement it as a means of authenticating into a device and automatically handle authenticating into any existing apps on the device.

This work was presented in a paper, titled The Memory Palace: Exploring Visual-Spatial Paths for Strong, Memorable, Infrequent Authentication (Sauvik Das, David Lu, Taehoon Lee, Joanne Lo, Jason I. Hong), at the ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST 2019), which was held Oct. 20-23 in New Orleans.