Algorithmic Aftermath: Researcher Explores the Damage They Can Leave Behind

Algorithms might appear harmless, but some of them are far from it. They gather information and make calculations, but whether they do so in a neutral manner is a debated issue.

The harmful effects of an algorithm can range from labeling and categorizing someone into a box that inaccurately depicts who they really are, to altering one’s future because of the way they answered a question on an exam or job application.

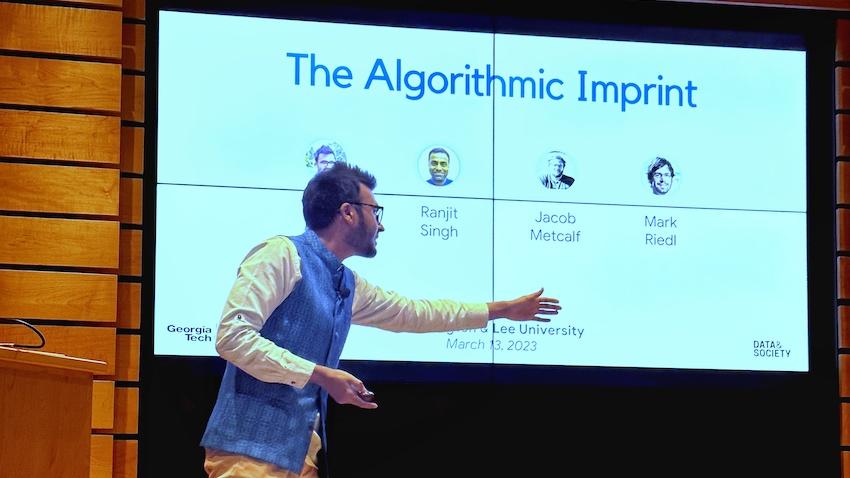

In some cases, algorithms can reinforce systems that are unjust or oppressive, argues Georgia Tech researcher and School of Interactive Computing Ph.D. candidate Upol Ehsan in his paper, The Algorithmic Imprint, which was presented at the 2022 Association for Computing Machinery’s FAcct Conference.

In 2020, Ehsan saw a news report about protests occurring in the United Kingdom. Students across the U.K. spoke out against the results of the General Certificate of Education (GCE) A-level examinations, which had been graded by an algorithm for the first time. The A-levels are the final exams taken before university in the U.K. and have a major impact on whether students can attend their desired institutions.

The Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual), the GCE exam governing body in the U.K., said the COVID-19 pandemic had made it necessary to pivot from manual grading to using an algorithm. Protests demonstrated that students found this change to be unacceptable, arguing the algorithm was biased against people from poorer economic backgrounds.

Ofqual removed the algorithm from its grading, but that didn’t solve the problem. Ehsan and his colleagues argue the effects of Ofqual’s algorithm lingered long after its removal. The situation is one example of how algorithms can leave hard imprints on the societies in which they are deployed.

“Most students we interviewed for the paper had their grades improved,” Ehsan said. “But they were still angry. That’s when I started thinking, ‘Why are people still angry even if their results aren’t bad?’”

And why was the U.K. the only country to receive any media coverage when the same exams are administered in more than 160 countries, including Ehsan’s home country of Bangladesh?

“This is not a U.K. issue,” he said. "This is a global issue. If we don’t share people’s stories, their narratives get erased from the historical narrative. If we didn’t bring this up, largely speaking, the Bangladesh narrative would’ve never been captured as the catastrophe that it was.

“Protests were also going on elsewhere. It’s just that they were never covered. These kids were protesting just as much as the U.K. kids.”

The fact that many of the other countries who use the GCEs are members of the Commonwealth — meaning they were once occupied by the British Empire — wasn’t lost on Ehsan.

The voices in the Global South weren’t being heard after suffering the effects of an algorithm designed by the Global North.

“Right now, the current way we evaluate an algorithm’s impact is from the birth to the death of the algorithm, from its deployment to its destruction,” Ehsan said. “When an algorithm is deployed, we do an impact assessment. When it is no longer deployed, we stop it, and that’s where we think this is the end.

“And that is the fundamental flaw in our thinking. Even when the algorithm was taken out, its harms persisted.”

The imprints can be even more damaging when they mimic or reinforce modern and historical systems of discrimination and oppression. Ehsan argues that was the case with the Commonwealth nations who also use the GCEs, and the exams were already considered to be unfair and biased before the algorithm was deployed.

“It feels like I’m paying money to my ex-colonizer for a piece of certificate that tells the world I am no dumber than a local UK kid,” said one student whom Ehsan interviewed during his research. “Sometimes it’s hard to ignore that reality.”

Ehsan compared the effects of colonialism to trying to erase pencil markings from a piece of paper. Even after the eraser has been used, the traces of the pencil markings are still visible.

“One of the things you see in postcolonialism is that there are remnants of the British infrastructure that we still live with today,” Ehsan says. “Just because colonizers leave, does not mean colonialism has left. Just because an algorithm has left, doesn’t mean its impact has left.”

Ehsan said the goal of his paper is to bring awareness to the imprints that algorithms can leave so developers can consider the potential impacts of an algorithm before deploying it.

“One of the things I wanted to do was drive policy changes,” he said. “I didn’t want this to be a research project just to have a research project. I had a moral reason behind it. I was driven by it.”

Ehsan also said he would like to see developers, researchers, and practitioners design algorithms in a way in which their impacts can be controlled and mitigated, and if an algorithm harms a group of people, reparations should be considered to atone for the damage.

“Algorithms leave imprints that are often immutable,” he said. “Just because they are made of software, it doesn’t mean there’s an undo button there.

“We need people to understand that algorithms have consequences that outlive their own existence, and if that doesn’t bring us into a more mindful, ethical way of thinking about deployments, I’d be very sad.”

The Algorithmic Imprint was co-authored with Ranjit Singh and Jacob Metcalf from Data & Society Research Institute and Professor Mark Riedl from the School of Interactive Computing.