New Privacy Research Hopes to Serve as Roadmap to Reform

When security and privacy is violated by data gathering companies, calls for reform from victims often result in little to no change due to a lack of agreed demands and a misalignment between experts and the public.

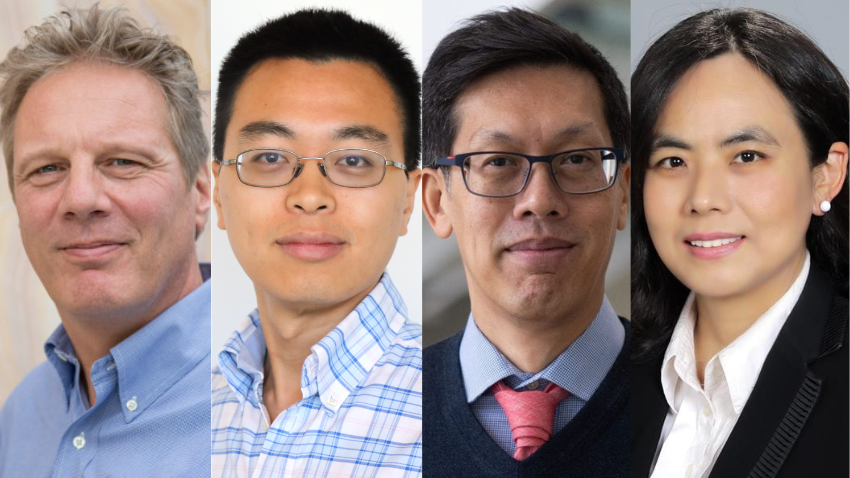

To help solve this problem, Yuxi Wu, a Ph.D. student at the Georgia Tech School of Interactive Computing (School of IC) explored designing a system that guides people affected by institutional privacy violations toward making unified demands for redress. Wu will present the research at the ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 2022) on May 2.

The paper investigates issues of representation and stewardship that appear when a collective wants change. Wu and her co-authors note that in the cases reviewed by their team, advocacy efforts failed due to a lack of debate and agreed solutions in internet petitions. Unclear goals and a lack of technical knowledge creates a rift between those affected by data breaches and the experts who can create solutions.

“Tons of people go on the internet to complain about these breaches and maybe a few petitions go truly viral,” Wu said. “But the original authors weren’t thinking of thousands of people when they wrote them. There is no good way to have a true discussion and present a united front as a collective.”

For example, in the wake of the Equifax breach in 2017, several petitions were started online. One of the biggest has close to 250,000 signatures with more being added, but it hasn’t been resolved.

The petition in this case states once it has reached 300,000 signatures it will be sent to several federal organizations including a federal judge who ruled on the case in the summer of June 2021. It is also worth noting the creator of the Change.org petition has not made an update in three years.

To explore how to improve on the dead ends of petitions, Wu and her co-authors developed their own version of a find-fix-verify process to corral people toward consensus. They recruited 400 online participants to identify concerns in response to an institutional privacy violation, come up with demands from these concerns, and vote on the most pressing demands. The participants eventually voted for 12 demands.

“People are really angry with big institutions, and they want to talk about them,” said Wu. “It is really difficult to translate these broad concerns and demands into specific actionable priorities.”

To help with mapping these demands onto the real world, the researchers then consulted a panel of eight security and privacy experts.

“The experts did share some agreements with the crowd: they recognized the harms that users faced was painful and hard to deal with,” said Wu. “However, they disagreed with the actions being demanded of institutions.”

A major disconnect between the two groups came from experts deeming the demands as unrealistic. However, Wu points out that experts’ deep knowledge of and entrenchment in the very institutions that collectives are fighting against might also make them dismissive of collectives. As a result, she hopes that future design work can examine how to address this tension, and how experts might in turn be assessed by collectives.

“A Reasonable Thing to Ask For”: Towards a Unified Voice in Privacy Collective Action was written by Wu along with her academic advisors Keith Edwards and Sauvik Das.