Students Collaborating with Nonprofit to Reduce Bird Collisions with Buildings

In 2015, before the cleaning crews hit the sidewalks of downtown Atlanta and before scavenger animals arose to snag an easy meal, Adam Betuel would venture into the darkness of the early mornings to look for birds.

Some were still alive, but most of the birds were dead. They were all too easy to find.

“I knew birds hit buildings, but I didn’t know much more about the issue at that time, and I was surprised how easily I just found birds,” Betuel said.

Birds flying into windows aren’t isolated events. Environmentalists estimate between 365 million and one billion birds die each year from colliding with structures in the U.S.

“That statistic is hard for most people to comprehend,” Betuel said. “When you think about the millions of homes we have and these high-rise buildings, and if each one is killing a few a year, that number can get big pretty quick.”

Betuel is the executive director of Birds Georgia, a nonprofit affiliate of the Audubon network that leads bird conservation efforts in Georgia. For 10 years, volunteers from the organization have combed Atlanta’s streets, collecting bird specimens.

Birds Georgia launched Project Safe Flight in 2015 to reduce bird building-collision mortality through data collection. Through legislation, the group aims to make building construction bird-friendly and reduce light pollution.

Environmentalists who study the issue have ranked Atlanta, which sits squarely on a migration route, as the fourth-most dangerous city for birds during fall migration. It is the ninth-most dangerous city during spring migration.

The number of bird deaths from collisions in Atlanta and across the state remains unknown. However, new data tools developed by student researchers in the College of Computing at Georgia Tech are helping Birds Georgia get a clearer picture of the issue.

“We’ve been working with different folks at Georgia Tech for years now, but it’s really picked up lately,” Betuel said. “There’s a lot of momentum and interest on campus to try to make the city safer for birds.”

Pushing for Policy

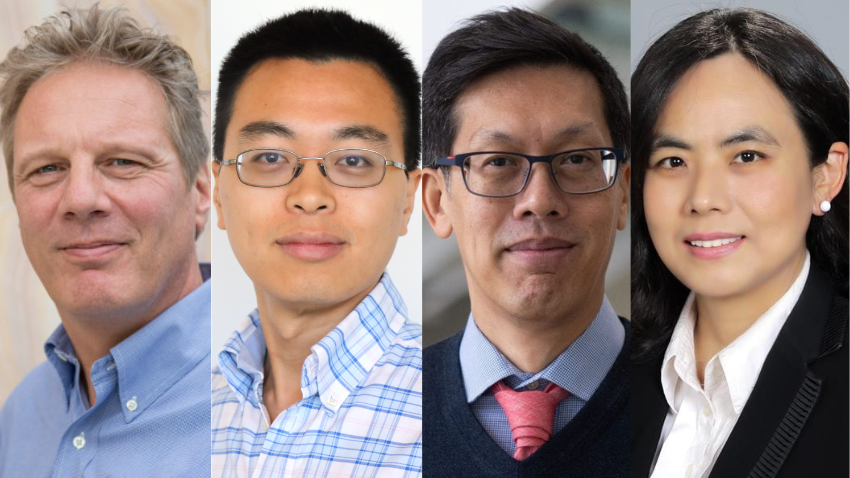

Ashley Boone, a Ph.D. student in human-centered computing in Tech’s School of Interactive Computing, has led the student effort to help Birds Georgia organize its data.

Boone said organizing data and knowing how to use it is critical to spark conversations about adopting legislation.

“We often see a gap between data collection and data advocacy,” she said. “Birds Georgia has done an amazing job of tracking collisions in Atlanta over the last 10 years. My goal is to understand the role technology can play in making data useful for policy change.”

User-interface tools designed by computer science undergraduate students James Kemerait and Ian Wood have ramped up that process. One tool converts data input into visualizations optimized for social media, while another consolidates the data collected by volunteers and external sources.

Boone said the desired legislation would mirror policies implemented by New York City. Those policies require the use of bird-safe materials — like window film with patterned designs that break up reflections — in new buildings and buildings undergoing significant renovations.

What Can Residents Do?

Residents, whose homes account for about 40% of bird collision deaths in the U.S., can also make an impact.

“Households are an underexamined cause of bird collisions,” Boone said. “We focus on the big buildings because it’s easier to convince one manager of a large building to use bird-safe materials, and it’s easier for a policy to address a commercial building. But the sheer volume of residential buildings in the U.S. has a tremendous impact on the number of collisions.”

Steps that homeowners can take include:

- Buying bird-safe film or making do-it-yourself versions of it to put on windows.

- Placing attractive objects like birdhouses and birdfeeders very close or very far away from windows.

- Turning off lights after 9 p.m. on the busiest migration nights of the year.

Betuel said millions of birds can fly over Atlanta on a single night during migration, and they are attracted to the city lights.

“They’ll come into urban centers and collide with an illuminated building, or maybe they overnight somewhere that isn’t safe,” he said. “The next day, they’re surrounded by glass, and birds don’t understand reflection.”

Residents can visit the Birds Georgia website to sign up for the Lights Out Pledge. Those who sign up will receive a text on the 10 busiest migratory nights of the year, and they will be asked to turn their lights off early.

The tools provided by Georgia Tech gave Birds Georgia insight into the number of bird species affected by collisions — more than 140, according to Betuel.

Betuel said that when the organization reaches an estimate of bird collisions, he hopes the number will raise alarms and turn people’s attention to the ecological impact.

“All these birds being lost results in fewer birds to eat pest insects, fewer birds to pollinate flowers, fewer birds to disperse seeds — all the ecological functions that we need, that they’re doing in the background that most people aren’t keen to,” he said. “If this decline in bird life continues to happen, at some point there will be issues with our ecosystems functioning how they always have.”

Main photo: Ashley Boone, a Ph.D. student in Georgia Tech's School of Interactive Computing, is leading a student collaboration with Birds Georgia to organize bird collison data. Photo by Terence Rushin/College of Computing.