Through Another's Eyes: University Researchers, Facebook Release Massive Dataset to Expand Innovation in AI

Imagine a collection of assistive technologies that could help a user learn a new skill, assist an elder individual with a task around the home, or help detect autism in early childhood. There exists an endless list of possibilities where artificial intelligence could impact humanity, but to do so it must see the world as we do -- in the first person.

A consortium of universities brought together by Facebook AI, including Georgia Tech, has collaborated to compile the largest dataset ever collected on egocentric computer vision -- or computer vision from the first-person point of view. With enormous application in the space of artificial intelligence and robotics, the project – called Ego4D – will inform and expand foundational research into assistive technologies that impact users at home, in health care, and beyond.

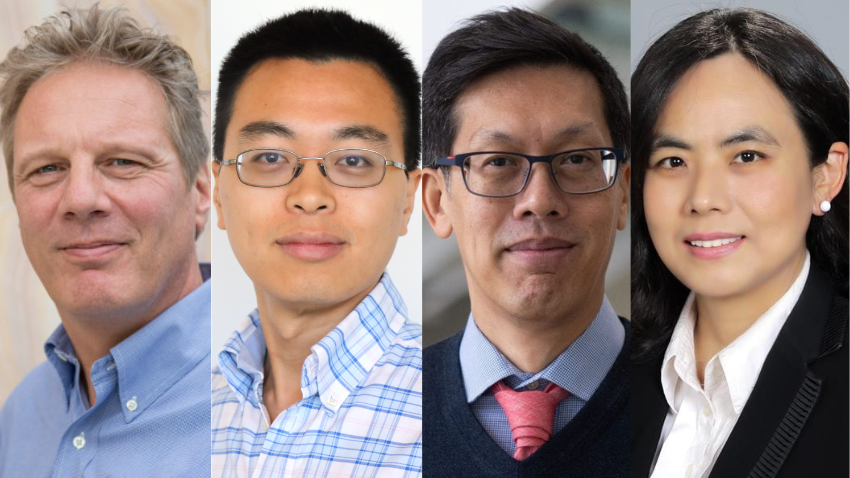

“At this point, we’re nowhere near being able to make functional assistants, but that’s what this dataset is motivated by,” said School of Interactive Computing Professor Jim Rehg, the leader of Georgia Tech’s team of researchers and the social benchmark team within the consortium. “We want to create capabilities to help people in their daily lives, and this is fundamental research in computer vision leading toward that goal.”

Egocentric vision is a specific field of research that analyzes video captured from body-worn cameras. Rehg and his Georgia Tech colleagues have long been leaders in this space, collecting an influential dataset on activity recognition and developing gaze measurement technologies for autism research.

Much of the early detection of autism is predicated on analyzing non-verbal communication in young children. Using body-worn cameras allows researchers to capture and examine video of social interactions in real-world settings.

“It’s much more convenient if you can tell a parent to wear this when they interact with their child for 20 or 30 minutes a day and then put it away,” Rehg said. “It’s not capturing aspects of your life you don’t want to share, it’s not in a lab setting. It’s much more natural.”

The problem for creating technological solutions to real-world challenges in health care or assistive technology, however, has been the inability of individual researchers to capture the kind of large-scale diverse datasets needed to train systems that can work for people of different needs, backgrounds, or cultures. Past datasets have been too small and tended to be from specific kinds of settings in the United States.

Rehg, along with researchers at peer institutions, decided to fill this gap by working together. The result has been much more widespread data collection, especially in locations like Africa, India, Saudi Arabia, and others around the world.

“All these things have come together in the creation of this dataset that we’ll be able to share with the research community,” Rehg said.

The dataset, which will be released in November, was collected by 13 universities and labs across nine countries and contains more than 2,200 hours of first-person video. It presents a diverse mixture of tasks around interaction with objects – cooking, gardening, construction, or knitting for example – and people interacting with their environment by manipulating objects to create things.

The idea is that with enough data, algorithms that can assist or predict needs on everyday tasks could then be developed.

“Imagine folks who are vision impaired, for example,” Rehg said. “They might not have the ability to see exactly what is happening, but if a system knew what you were trying to do it could possibly alert you to things that might be relevant. For example, if you’re mowing your grass it will know that you don’t want to collide with trees or run over things that are harmful to the mower.”

Georgia Tech’s interest in this space aligns with the focus on health-related applications. Rehg provided one example of potentially helping individuals with hearing impairments by developing hearing aids with the assistance of AI to improve selective attention.

“Often hearing aids just amplify all the noises in an environment, including those in the background,” Rehg said. “Imagine if AI could help provide some tuning on that through an agent that understands social interactions – when someone is looking at you, when they are talking to you.”

These collaborations between computer vision and researchers in other spaces, like health, are vital to solving many challenges individuals face in their daily lives, Rehg said.

Partners in the consortium include researchers at IIIT Hyderabad, Indiana University, University of Bristol, University of Catania, Facebook AI, KAUST, Carnegie Mellon and its campus in Africa, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, University of Minnesota, University of Tokyo, University of Pennsylvania, National University of Singapore, and the University of Los Andes.

In addition to Rehg at Georgia Tech are Ph.D. students Fiona Ryan (School of Interactive Computing) and Miao Liu (School of Electrical and Computer Engineering), master’s student Wenqi Jia (College of Computing), lab manager Audrey Southerland, and research scientist Jeffrey Valdez.