New Software Could Improve Diabetic Foot Care

When it comes to developing computer solutions to social issues, School of Interactive Computing Associate Professor Rosa Arriaga looks to tell the stories of groups who are overlooked and underserved.

A new app Arriaga has in development amplifies the voices of patients with diabetes and diabetic foot ulcers — a severe complication for more than one third of people living with diabetes that often goes unaddressed until it’s too late.

If left untreated, a diabetic foot ulcer can become infected and lead to amputation. Arriaga’s app may be the tool that prevents the situation from ever coming to that. The app detects the presence of ulcers and tracks whether the conditions of the ulcers worsen.

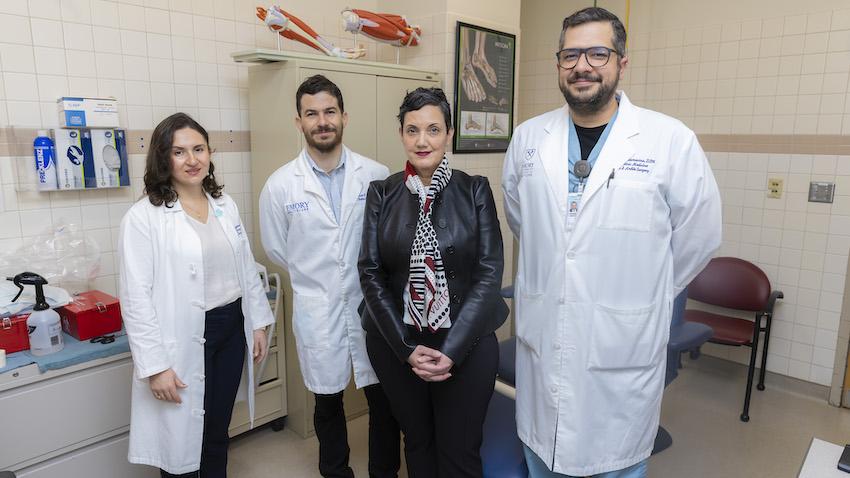

To create the app, Arriaga partnered with researchers and doctors from the Emory School of Medicine and Grady Memorial Hospital. Their work caught the attention and support of the American Diabetes Association, which awarded them with a grant in January.

Arriaga and her collaborators were also among the first recipients of the A.I. Humanity Seed Grant Program, a collaborative effort between Georgia Tech and Emory University to expand partnerships and leverage artificial intelligence to improve society and quality of life.

“I had never come across diabetic foot ulcers,” Arriaga said. “The way I do research, I try to think of what the gold standard of care is in each domain, and then I think about how computing can help. This is that sweet spot where we can address a big problem and make an impact with relatively simple computing.”

Arriaga calls it the Diabetic Ulcer Computational Sensing System, which can be accessed through a mobile phone. It requires patients to use their phones to perform a foot health exam — documenting the condition of their skin, their sensations, their circulation, and their walking gait. Patients can also have a caregiver do these things for them if they are physically unable.

Who is at risk?

The looming problem of diabetic ulcers did not escape the attention of two assistant professors at the Emory School of Medicine: Maya Fayfman, who works in the Division of Endocrinology, and Marcos Schechter of the Division of Infectious Diseases. Working alongside Dr. Gabriel Santamarina, director of podiatry at Grady, they noticed the increase in amputations at Grady and how many of those patients came from underserved communities.

“Despite recent advances in diabetes treatments and improvements in other complications, diabetic foot ulcers and amputations are at best stable and by some measures on the rise,” Fayfman said. “They disproportionately impact people who are of the lowest means and suffer most from loss of mobility and inability to work.”

Many patients with diabetic foot complications don’t seek treatment because they don’t have the means to go to the doctor for checkups. The new app tackles this problem head on and allows patients to examine their affected foot and send results to their doctor remotely. The doctor can then determine whether the ulcer poses a threat of amputation. Arriaga said she hopes to add an algorithm to the app that can detect when the condition of an ulcer has worsened.

How ulcers go unnoticed

In addition to neglecting or not being able to access routine care, patients with diabetes often develop neuropathy, which can cause loss of feeling in the feet of diabetic patients. If a patient suffers a wound on the bottom of their foot, neuropathy may cause them not to feel it, and the wound can expand and become infected.

“People with healthy feet who develop an injury in their foot will adjust how they walk so they don’t apply as much pressure,” Fayfman said. “That pain is helpful in promoting healing. In patients with diabetes, that loss of sensation makes it so they’re not recognizing the pain, and their wounds get worse before being recognized.”

Schechter said increased awareness could go a long way to not only preventing amputations but saving lives. Diabetic patients are already immuno-compromised, and amputation leads to immobility and a decreased ability to fight illnesses, increasing the risk of the problem becoming fatal. Published research shows that the mortality rate for people who lose a limb due to diabetes is 70 percent within five years.

“A lot of people, when they come to us, the ulcers are very severe, and the limb can’t be saved,” he said. “If people could monitor this with pictures at home, and they could share these pictures with providers, or the app could predict whether this ulcer needs care right now, maybe that can prevent people from coming in with advance stages of the disease.”

A hub for communication

While the ADA is helping to fund the development of the app, the team believes the grant is an overdue step toward raising awareness about the seriousness of diabetic ulcers.

The researchers conducted a focus group of patients with ulcers and amputations and learned that many had never heard of diabetic foot ulcers before being diagnosed with one.

“That to me is the saddest part,” Arriaga said. “Some people are saying they were never told about it. On the one hand, that’s not comprehensive care, and on the other hand, the doctor must get to the biggest thing — let’s make sure we work on your sugar if you can only work on one thing. It all goes back to a fragmented health system.”

One of the app’s goals is bridging those gaps within the system by providing the opportunity to improve communication between patients and the doctors who treat them. Reducing redundancies in the system will lead to more affordable care while keeping patients and providers informed of the progression of ulcers.

“I think an ecological approach to diabetes care is essential for optimal health and wellness,” she said. “It is not enough to task one group of stakeholders with managing diabetes. Technology can connect the various stakeholders (i.e., patients, their caregivers, clinicians) so that diabetes foot care can be streamlined. It can also improve knowledge about foot care and alleviate the negative outcomes associated with foot ulcers.”